If one was to compare the display conventions of the Pinakothek’s contemporary jewelry collection to that of other international art museums, there is an obvious standard. Although the Pinakothek’s devoted environment is extremely spacious and impressive, the shared standard is still a banality that unfortunately extends its reach all too often. Whether elevated off the ground on pedestals or vertically assembled against a wall, seeing works in jewelry behind glass is almost always the norm (the MFA Boston, MAD NYC, the V&A in London, click —> here for a nice video about the Pinakothek’s collection…). It can be said that the usually plentiful pieces that make up a series for exhibition have to be installed; the space is curated in a straightforward manner that normally remains indifferent to the work and its ideas as dictated by the limitations of the cases. It’s a unique problem, summarized well by Liesbeth den Besten in her book, On Jewellery, A compendium of international contemporary art jewellery.

The museum showcase stresses the preciousness and uniqueness of a piece of jewellery. When an object or a piece of jewellery enters a museum collection its appreciation is changed. Its significance has increased but so has its isolation. The glass vitrine hinders the creation of meaning : the object now has an art status.

But does it really, or is it a perfunctory illusion? Does gaining an art status really mean obscuring the object’s very own conceptual underpinnings? No, I don’t think so, yet in the case of jewelry it is an excepted turn of events. One could argue that the museum’s role is to enhance the qualities of uniqueness, not push them back, yet if the artist does not present this necessity, and many do not, then how much framing of the work is required of the museum as an institution? This is where my head starts to hurt. It’s like thinking about space or something, posing questions that no one can really answer. If one refers to my “Cosmology” of contemporary jewelry, there are arguably very different categories of work being made in the field, all with different motivations that extend beyond the guise of the word jewelry. As Stefano Marchetti recently told me, some work dies behind the glass, and some work dies outside of the glass. Considering all of that while also understanding that the potential life of any jewelry work is so much more infinite than a painting’s for example (sure, you can put the painting anywhere, but a jewelry work can be taken anywhere and simply given to anyone and so on and so forth), is where things get even more complicated. Interestingly enough, this aspect does add to the uniqueness of our field, just like its inability to be easily defined, explained and labeled. I often wonder if individual preference by artist is being met, or in which ways the artist values the lives of their pieces (I have an old blog post that address this issue a bit, read it —> here). Are museums really doing the individual pieces justice? Depends on who you talk to. Perhaps the museum’s most pertinent role thus far is to simply yell, “HEY, YOU! THESE THINGS EXIST!”

Step by step by step.

Also in the Jewellery Talks film, art historian, curator, writer and lecturer Mònica Gaspar Mallol, talks about the duality of life inside or outside the glass.

Well, if I have to tell you my background, I come from a family of art gallerists, so for me art was something always hanging on your wall or something out of your reach. I was always interest in what you can use and what you can touch and what you can make your own. So I think that since I finished my studies in art history, I went directly for this field, I didn’t have an intermitted stage with other disciplines. That’s always a very interesting conflict that not only jewelry, but any object has. The moment you put something behind the glass, somehow you betray the nature of the object. You make it sharable, you can show it with the rest of the world, but the whole nature of use, of meaning and attachment with the owner or with the collector, somehow gets lost. So I think it’s very interesting the potential that jewelry has being worn on the body, which is almost the worst place to appreciate the piece of jewelry, it’s the worst place you can put an object to really see it and understand it because the body is in movement, you have so many other inputs that can distract you from the perception of the object; it’s very interesting and very paradoxical that the body actually is the best place.

Ok, so if we’ve decided that the museum elevates the work to an art status by negating the very idea behind it, when do others get to fully understand the power of the artwork? Islanders (remember, contemporary jewelry as a small and uncharted island) recognize the potential of the work, as they see time, thought, research and tactile relationship without having to touch. Chances are they know a little (or a lot) about the person who made as well. To islanders, the glass remains satisfactory, after all, their piece is in a museum. If Monica Gasper is right, the body isn’t necessarily so ideal as a place of exhibition either. Of course everything changes and it goes far beyond the technical problems of movement, etc that she mentioned. It’s also likely that the average person never actually gets to touch or wear or experience the piece to begin with; it’s an all too rare exchange left to collectors/buyers whether independent or from other contemporary jewelry galleries. More talking to ourselves. If it isn’t in the glass case and it isn’t on the body, then where the hell is it that those on the outside get to fully understand that these objects are more than precious relics or avant-garde accessories?

THE ROLE OF THE GALLERY EXHIBITION

As a city and center for quality museums and contemporary art, Munich also boasts some well-known contemporary jewelry galleries within its mix. In the case of Schmuck, additional spaces are created to house collateral gallery events, either as extensions of existing international galleries or independently run pop-ups. Because this entry serves to reference the specificity of Schmuck, it will avoid commenting much on the bigger name contemporary jewelry galleries that usually participate in Schmuck’s fair-like aspect; this year Galerie Marzee, Galerie Ra (Holland) and Platina (Sweden) presented themselves in this sense with set-ups adjacent to the Schmuck exhibition in the Handwerkmesse. I will also note that in general, the roles of these established and often quasi-historical galleries serve more similarly to that of the museum and are part of their own, unique system that includes a few exceptions to that very system.

Two of the more known Munich-based jewelry galleries that I was able to visit during Schmuck week were Galerie Handwerk and Galerie Spektrum, showcasing contrasting yet equally interesting exhibitions, despite my resistance to believe so. Handwerk’s show, entitled Die Renaissance des Emaillierens, boasted a list of artists too long to name (click –> here), all of whom are making innovative works with enamel. Usually with a list that extensive I normally get a bit… frustrated, yet all of the work seemed to be carefully selected so as not to appear that the gallery simply invited every single artist living on the island who uses the stuff (even though they might have). Enamel use is a common traditional element in jewelry that doesn’t see the light of day much anymore and obviously it was the exhibition’s common denominator. A show based on material is usually another ingredient for frustration but somehow frustration never ensued. Perhaps it was because most of the selected artists seemed to transcend the qualities of the material in contemporary modes, as enamel can easily connote a statement of “I’m old, irrelevant and boring.” Here is where the show rationalizes itself, an example of good curation even within a theme as banal as “what the pieces are made of.” Other antidotes to a headache include a combination of the gallery’s size (the space is enormous and spans two stories with an open floor-plan), the quality of the individual work, and the space given around each piece. Nothing was overcrowded, as it tends to often be. The gallery clearly respects the work, even though the pieces were once again bound to glass vitrines.

Here I find myself a living contradiction, as again, I was not releasing steam as I moved around the space peering into the protective display cases. I imagine this was so because Galiere Handwerk does not proclaim to be a mecca for contemporary art jewelry. It is not trying too hard to experiment with “new” display that often ends up being just as boring and unconventional as the traditional predecessor. In this sense, Handwerk acts more like a museum while employing a much greater level of education and communication because it is indeed a gallery, with someone present to talk to you about the individual works. Here is Galerie Handwerk’s blurb, absent of fuss and grounded in a special locality:

A showcase for Bavarian trades and crafts, the gallery is devoted to conveying to the general public an idea of the outstanding skills of today’s craftsmen and women and the contribution they make to society.

Mounting seven exhibitions a year, the Galerie Handwerk gives the crafts a highly visible presence on the Munich scene. The exhibition topics reflect all the diverse functions of the crafts in culture and society. They range from applied art and artisanry, through the trades and architecture, the maintenance of protected monuments, and folk art, down to design education and training curricula in the trades. The presentations cover traditional, classic and avant-garde approaches. And they extend beyond regional developments to those taking place on a national and international level. As this implies, the gallery makes a significant contribution to the dissemination and advancement of artisanship worldwide.

Fine, great even. I suppose one could say that Handwerk views this jewelry work to be that of the avant-garde. As it was a good opportunity to see pieces in person (however limited) by legendary and upcoming artist/jewelers (Pavan, Marchetti, other Italian greats alongside more internal and personal works by Carolina Gimeno and Kaori Juzu, just to name a few) Handwerk’s model as a gallery is old and of little interest to my search for contemporary new platforms that want to showcase relational aspects of work being made in the field. Even so and speaking within a very jewelry as (just) jewelry perspective, it was an impressive collection at the very least. The gallery clearly values the pieces as precious relics, and that is not untrue, of course, but my interests are less of how jewelry remains to be related to tradition and craft, and much more of how the field also (or instead) relates to contemporary art.

In contrast to Handwerk, Galerie Spektrum plays in a different ball game that deals more heavily with the artist’s overall concept by aiming to exploit it. Generally, a better example of conceptual recognition within an exhibited series is almost always seen in solo shows, if one can nail one down.

Ruudt Peters’ exhibition Corpus showcased a ring of black cloaks hanging from the ceiling, an installation seen before at Galerie Rob Koudijs last September. Peters is known for taking advantage of space to communicate the fundaments of his works, which this specific installation certainly does. Historically speaking, Peters was one of the first to be recognized for new and innovative display conventions (in 1992 his Passio series, for example, included an exhibition where he also enclosed hanging fabric from the ceiling to the floor around the floating pieces so that one would have to gently find their way in to view the work).

If one was lucky enough to attend the opening at Spektrum on the Sunday afternoon in which the exhibition commenced, Peters was in attendance gifting fragmented brooches of the pieces on show to those patiently waiting in the long line outside. Spektrum is teeny-tiny, the line to get inside was inevitable. Instead of letting the special restrictions limit the extent to which Peters was able to expose the work’s social ingredients, he used it to his advantage. Here’s an excerpt from a recent interview I had with Peters with regard to how the performance quality in his actions can be seen as a singular artwork.

Ruudt: I asked everyone if they wanted a present, and then I gave one, and I said oh, you want –and I put it on your jacket or whatever, so I put it on everyone. But finally, I had this show of the Corpus Christi [on Sunday], and in every church on Sunday they give you the [eucharist]… I never can do it in my whole life again, a giving a present to someone, because then I kill my whole concept.

Me: And so do you see that act, that day, you doing that, as a work in and of itself?

Ruudt: Yeah.

Ruudt Peters is interested in building a bridge off the island, he always has been, with work like this serving as a testament. He values the power of his objects, they are charged and are made to charge others, both tactilely and tactfully.

Spektrum values this too. During my visit I spoke briefly with co-founder, Marianne Schliwinski, about installation from the perspective of the gallery. She talked about how the gallery always tries to get the artist to use the full space, as exhibiting at Spektrum is also an invitation for the artist to think about their work in bigger terms or how an installation can also be their work at the same time. Schliwinski said that the opportunity asks the artist to learn more about his or her own work and how it might exists in a new environment, which can be very insightful for the artist, the gallerist and also the public. She paralleled this to self-publication, “it’s like if you do a catalog by yourself you have to reflect about your work… it’s easier to get in front of these unknown people if you have an overview.”

The unknown people are the audience, the public, people who may or may not know so much about the generalities of contemporary art jewelry. Schliwinski wants to communicate to these unknowns and wants to make the information of the artists and the ideas behind the work assessable. Here might be an example of how we are not talking to ourselves.

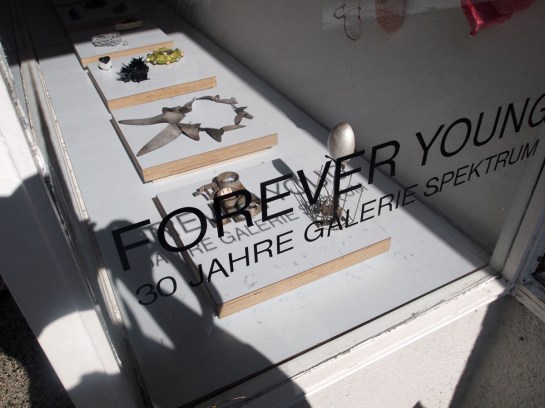

Interestingly, Spektrum hosted another exhibition simultaneously entitled, FOREVER YOUNG, 30 Jahre Galerie Spektrum (30 years Galerie Spektrum), a self-explanatory retrospective with corresponding photos of the gallery’s artists taken thirty years ago next two singular pieces in the outside display window. Works inside the gallery were crowded together on shelves behind glass, almost mimicking objects found inside a curiosity cabinet. Because of the nature of the show itself, a declared collection of pieces spanning three decades before, the display was forgivable and felt more like a treasure hunt or game of eye-spy.

Lisa Walker’s solo show GLEE at Galerie Biro, and Schmuck darling, Alexander Blank’s Totem on the Sideline at Galerie ARTikel3, were two more gallery exhibitions worth mentioning. I attended both openings; Blank’s happened to be quite a lot empieter than Walker’s due to the late hour of my arrival, yet thankfully so because I was able to see the artist and guests handling the pieces. Walker’s opening was literally shoulder-to-shoulder, and while she took a more conventional root display wise (walls with glass boxes, necklaces hanging on walls), there were a few pieces missing implying that guests were instead adorned. Walker herself could be found at the center of the small space with her elbow resting on an empty pedestal. I mention these two shows together due to their white box similarities yet willingness to pass the pieces around during the chaos that can be an opening event. This environment more accurately mimics that of a real life situation, as after all, jewelry is the everyday and is meant to be experienced.

As far as existing in a self referential island, these two shows had the potential to be bridge builders in their own way, mostly due to the strong and conceptual nature of Blank and Walker’s work. Blank offered a long and impressive press release (which was a text from a former exhibition at Gallery Rob Koudijis written by Keri Quick of AJF) discussing his series in a way that wasn’t confined to the world of jewelry or its history. Instead, Blank’s objects and Quick’s text speak to a universality that in turn rationalize the work’s own existence. More importantly, the verbal framework show a willingness to speak to new audiences while the anonymity of the gallery helps as well (like Spektrum, Walker’s gallery, Biro, is described as a jewelry gallery).

I would like to continue this post, yet due to a fear that it is already too long to hold your attention, I will post a part three, in time. Schmuck exhibitions still to mention will be group show, Suspended at Studio Gabi Green, Volker Atrops’ No Stone Unturned, Mia Maljojoki’s Crossing the Line, Galleria Maurer Zilioli’s showcase of artists Elisabeth Altenburg and Wolfgang Rahs, Returning to the Jewel is a Return from Exile (Robert Baines, Karl Fritsch, Gerd Rothman), the Royal Academy of Fine Arts Antwerp’s exhibition The Sound of Silver, group shows What’s in a Frame? and Pin Up.

JEWELRY

JEWELRY