As I try to piece together visual epochs in Italian art history, it has been a bit challenging knowing where to start. As such I feel it necessary to reiterate the question I posed in one of my previous blog entries. How much do I need to know… to know? This question is bound to be reoccurring, and unfortunately there is no answer here. The best one can do in such a situation is close their eyes and pick… somewhere, anywhere– as the solutions are infinite, and quite frankly, there is no wrong path to take…right? I hope so. Doesn’t anything teach you… something?

Let’s start with neoclassicism, shall we? As part of my research proposal I was granted access to use the library at the American Academy in Rome on the top of the Gianicolo. Here would be a fabulous spot in which to digress, as Monte Gianicolo is quite breathtaking as well as the academy itself, but let’s keep going. Finding this book, The Geometries of Silence by Anna Ottani Carina was accidental. Perhaps I should fib a little and pretend that I fully intended to begin with the neoclassic era in my research; either way it suits my interest in piecing back together Italy’s visual lineage, as the neoclassic era by nature, more or less, did exactly that. I must mention that this piece of writing will function as a summary of notes I took on the text in combination with my own feedback, thoughts and questions. Things that I have decided are really important will appear in bold.

Carina, the author, begins to summarize the foundations of the era and credits of course, the revival of antiquity (again!!) that followed the resurrection of buried cities like Pompeii in the mid 18th century. Similar discoveries ultimately led to the neo-revival of living “in the ancient style”. According to Carina, a new geometrical image of the city was created. Because this all happened in Italy, an unattainable perfection of the ancient world burdened Italian artists, in comparison to the dozens of Northern European or non-Italian artists who responded more quote-unquote positively. Carina describes this as the “double valence” of the ancient model—non-Italians embraced reason, history, and the persistence of the classical world, while Piranesi (an Italian!) for example, responded in a more irrational and subconscious manner.

Piranesi was one of the few artists that reacted negatively to the past, and by Carina’s logic, it was because he was an insider. I think the words positive and negative only reference a state of mind—the words can more accurately be described as reactions made by the artists that uniquely lead to manipulations and different interpretations of the visual past. The true question is, in which of these reactions lead to innovation? In which ways was the past fuel for these artists? Carina poses some questions that help to define the way the newly uncovered past could act as contemporary inspiration. Was the past a reassuring or positive myth whose authority served as a guide and a creative stimulus? Or was it a barrier whose presence paralyzed the creative impulse? The answer can perhaps be dictated by the origin of the artist.

In the mid 1770’s artists shared a common notion of ANTIQUITY AS FUTURE whether voluntary or involuntary. For some, the past was once again an intended model for aesthetic renewal, but for those like Piranesi, the weight of the past infiltrated the work in other ways. He saw the past as a burden, a perfection that could not be surpassed. In my opinion, this is where innovation and ultimately modernization struck. Carina states, “antiquity was therefore conceived as the future, in which the past, projected ahead of time, became the model for aesthetic palingenesis.” Like in the Renaissance, artists once again attempted to appropriate history and tradition in contemporary ways. Yet unlike the Renaissance, I believe a duality of accessibility and inaccessibility differentiate the eras and the work that was made. I will attempt to explain.

Archaeological excavations spurred an excitement in Italian and non-Italian artists alike, obviously more so for foreigners (the start of the Grand Tour, sketches of archeological ruins by other European artists, etc). And for the first time in history, these artists were able to see the entire site, the entire foundation, the entire fresco, etc. The visual information available during the Renaissance in comparison was more fragmented, more limited. This created repetition in artists that followed the old style, seen Raphael’s grotesque loggias in the Vatican (1517-1519) for example. His work here with others like Giovanni da Udine, Giulio Romano and Baldassare Peruzzi suggest a maximum stylization of relationships in their surfaces taken from these limited ancient fragments. But 200+ years later during the neoclassic era, more of the visual past was available. This may imply more straightforward replication, a potential for little interpretation or innovation, however within this new accessibility existed an aspect of inaccessibility that in turn led to different results detached from the originals. This is because artists were not actually able to view the uncovered originals of antiquity for a significant amount of time. If they were even granted access to the sights (Pompeii and the Herculaneum or Ercolano) it was extremely limited, and they sure as hell weren’t able to sketch or take note of anything. Artists then literally had to go home to recollect and draw from memory, which in turn, created visual degrees of separations from the original models, especially when artists fabricated the completion of old ruins themselves, based on fantasies or personal aesthetic and ideas. This was true for the uncovered ruins and frescos, as well as vase paintings, according to Carina. More or less unintentional, “rather than a correct interpretation of antiquity, these episodes amounted to a betrayal of it.”

Archaeological excavations spurred an excitement in Italian and non-Italian artists alike, obviously more so for foreigners (the start of the Grand Tour, sketches of archeological ruins by other European artists, etc). And for the first time in history, these artists were able to see the entire site, the entire foundation, the entire fresco, etc. The visual information available during the Renaissance in comparison was more fragmented, more limited. This created repetition in artists that followed the old style, seen Raphael’s grotesque loggias in the Vatican (1517-1519) for example. His work here with others like Giovanni da Udine, Giulio Romano and Baldassare Peruzzi suggest a maximum stylization of relationships in their surfaces taken from these limited ancient fragments. But 200+ years later during the neoclassic era, more of the visual past was available. This may imply more straightforward replication, a potential for little interpretation or innovation, however within this new accessibility existed an aspect of inaccessibility that in turn led to different results detached from the originals. This is because artists were not actually able to view the uncovered originals of antiquity for a significant amount of time. If they were even granted access to the sights (Pompeii and the Herculaneum or Ercolano) it was extremely limited, and they sure as hell weren’t able to sketch or take note of anything. Artists then literally had to go home to recollect and draw from memory, which in turn, created visual degrees of separations from the original models, especially when artists fabricated the completion of old ruins themselves, based on fantasies or personal aesthetic and ideas. This was true for the uncovered ruins and frescos, as well as vase paintings, according to Carina. More or less unintentional, “rather than a correct interpretation of antiquity, these episodes amounted to a betrayal of it.”

MODIFYING THE ANCIENT CANON

Now let’s talk about what came out of all this or at least try to mark the changes that were being made. It would be far too complicated to talk about what all the foreign artists produced after they came through Rome marveling the ancient ruins. What I am interested in is what changed in Italian art and how it evolved as such. How did Italians interpret their very own visual history as it was being dug up before them? Piranesi is an extreme example, an exception even (he was a genius!). But what was he looking at? Talking about what this man alone produced in the 18th century requires a completely separate piece of writing, but what I will mention is the fact that he was an engraver. By the mid century, Carina notes that artists became interested in recapturing how ancient Roman paintings possessed a concise way of defining form, and artists that were engravers further accentuated these qualities by the nature of the medium. “Selecting the motifs to be engraved meant selecting those elements that, to the people of the 18th century, appeared to be essential. The result of this process of abstraction was that the complexity of the pictorial substance became reduced to its mere outline. And like I said before, access to the original sites and objects was limited, and artists then looked and copied from these engravings of ancient ruins or motifs. Here we have more degrees of separation. What begins to appear is a new minimal visual vocabulary from which to build on– an 18th century abstraction that focused on linear qualities. A combination of a lack of chiaroscuro that eliminated depth and dissociation from nature created more of an anti-realistic artistic language for artists. Carina mentions the fantastical yet knowledgable drawings of decorative painter, Pietro Antonio Novelli, when making this point.

What begins to appear is a new minimal visual vocabulary from which to build on– an 18th century abstraction that focused on linear qualities. A combination of a lack of chiaroscuro that eliminated depth and dissociation from nature created more of an anti-realistic artistic language for artists. Carina mentions the fantastical yet knowledgable drawings of decorative painter, Pietro Antonio Novelli, when making this point.

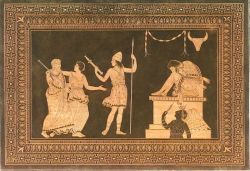

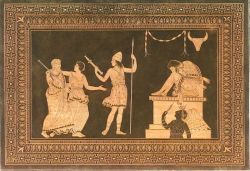

An example of this fragmented process can be seen in various reproductions of engravings copied from Etruscan vases. Some of these copies can be described as “far more advanced in the direction of linear abstraction than any paintings or drawings executed until the 1790’s.”  The concise and abbreviated style can seen in the reproductions included in the d’Harcanville catalogue (Collection of Etruscan, Greek and Roman Antiquities from the Cabinet of the Honorable Wm. Hamilton 1766-67. The catalogue is a seminal work on Classical antiquities, mostly vases published in the 18th century), for example, may have been copied from Italian artists like Giuseppe Bracci (I am currently trying to find more information on him) and similar artists who first copied these vases, according to Carina. These images implied the work that was to come at the end of the 18th century that was executed in a new “conceptual style” able to “breakdown the perception of the image based on the illusionary optics introduced by the Renaissance.”

The concise and abbreviated style can seen in the reproductions included in the d’Harcanville catalogue (Collection of Etruscan, Greek and Roman Antiquities from the Cabinet of the Honorable Wm. Hamilton 1766-67. The catalogue is a seminal work on Classical antiquities, mostly vases published in the 18th century), for example, may have been copied from Italian artists like Giuseppe Bracci (I am currently trying to find more information on him) and similar artists who first copied these vases, according to Carina. These images implied the work that was to come at the end of the 18th century that was executed in a new “conceptual style” able to “breakdown the perception of the image based on the illusionary optics introduced by the Renaissance.”

Now we have begun to establish an aesthetic shift and pinpoint some of the qualities found within ancient works that were to be developed, exaggerated or disregarded as the images passed through the eyes of different artists. Another example found within the work of an Italian can be seen in the creations of Felice Giani (1758-1828). Giani was a painter that specialized in decorative work, as he designed interiors while developing a unique ornate vocabulary. He used repetitive techniques, similar to the decorative work of Raphael and his team in the loggias, yet he is noted as someone who reclaimed preeminence or value in designing decorative interiors. Carina mentions that during his time (late 1780’s and onward) decorative painting was competitive. Due to minimal costs, excellence in application, and fast execution, innovation in style developed. And because Italian features were not easy to export (frescos for example were difficult to execute in places like England due to weather, so not only were they not replicated but they also were not frequently seen because they were commissioned by private individuals in residences), new more modern characteristics were unique to Italy. Other factors included an ongoing dialog with the patron, as interior spaces were custom built. The fascination with antiquity as future was a mutual interest valued by both artist and patron, and were rooted in a local Italian tradition.

He used repetitive techniques, similar to the decorative work of Raphael and his team in the loggias, yet he is noted as someone who reclaimed preeminence or value in designing decorative interiors. Carina mentions that during his time (late 1780’s and onward) decorative painting was competitive. Due to minimal costs, excellence in application, and fast execution, innovation in style developed. And because Italian features were not easy to export (frescos for example were difficult to execute in places like England due to weather, so not only were they not replicated but they also were not frequently seen because they were commissioned by private individuals in residences), new more modern characteristics were unique to Italy. Other factors included an ongoing dialog with the patron, as interior spaces were custom built. The fascination with antiquity as future was a mutual interest valued by both artist and patron, and were rooted in a local Italian tradition.

Like any good neoclassicist, Felice Giani was inspired by the relationship with the models of antiquity and the ways in which they were presented during the Renaissance. He was inspired by Raphael and his contemporaries, yet he further “intended to defend the new criteria of functionality and comfort against any showy or luxurious features”, made able by his concise and communicational strengths. He is described by Carina as being such an innovative artist that he was “able to undermined a hierarchical relationship that had been in force for centuries [painter, designer, decorator, architect, etc]…Giani revolutionized relationships.” This was in part to how he organized and directed his bottega, made up of men of many trades such as quadraturisti, sculptors, stuccoists, carpernters, etc. “Preeminence of the painter over the architect and the quadraturista that constituted the Italian variation of the theme of interior decoration, a variant where the leading role was reserved for painting.” This is important because decorative work has always been considered secondary, and again, the structure of the Italian workshop was unique to the rest of Europe. This is seen in site specificity of frescos (work in situ in Italy) and the much less hierarchical organization of roles; Giani’s workshop primarily dealt with decoration of a space and he did not work with metal, the building of staircases, fireplaces, or any of the interior architecture etc.

I think Giani was worth mentioning for a few reasons.

Reason one: decorators or designers of this era (or really any…) are rarely mentioned in art history. And since the work I do is roughly considered to be a cousin of such frivolous or minor art, I would also like to give this guy come credit for being relatively contemporary.

Reason two: Like I said before, Giani’s style was developed by the limits of his trade, insofar as the work was nonexportable and rooted in local traditions, branding it as specifically Italian.

Reason three: The decorative work of interiors is much less known in Italy in general and as such, great examples remain to be practically unknown. Those that are, tend to “possess particular characteristics and are frequently extraordinary,” states Carina. This I would say is because of the nature of the decorative arts, in combination with the philosophy behind neoclassicism. We can describe it as a summary, much like how the previously mentioned engraving examples were also summaries; definitive and specific reinterpretations that mark what was stylistically coveted by both artist and patron.

So how does Italy choose to summarize itself overtime? This bit aims to find specific attempts. The rest of the book, however, is about non-Italian painters and their respective innovations … but they were indeed, in Italy. What can we learn about Italy and the ways that it had existed in its past and relative present, that influenced innovation of the outsider? Is this important? Surely. But Italy’s inspiration was involuntary, a natural progression of sorts, that valued a traditional past and hand-made production. Carina references what is called a leapfrog syndrome, which occurs when a generation recognizes its cultural models in ancestral precedents rather than its immediate predecessors. The neoclassic era applies to this, yet couldn’t one argue that Italy’s immediate predecessors are its ancestral precedents, because of Italy’s maintenance of it’s own visualy history? Is there really any distinction?